• Building a Nieuport 11 replica •

• Design •

I wanted an aircraft that met the UK single seat deregulated 'SSDR' criteria, i.e. all up weight less than 300kg and stall speed below 35 knots. This keeps costs down and eliminates the need for complex and costly compliance procedures. I also wanted something with character, preferably a replica and a biplane. My preference was to build in wood as I had experience with and enjoyed working with this material.

In order to achieve a 35kt stall speed for a biplane, or a monoplane without flaps, you generally need a maximum wing loading of 25kg/sqm. At maximum gross weight of 300kg this means a wing area of about 12 sqm (129 ft2). (If you can achieve a weight of 275kg this falls to 11 sqm (118 ft2) and at 250kg it is 10 sqm (107 ft2)) This gave me a target weight and wing area to aim for when selecting a design.

I looked at all the available kits and plans available on the market, and also considered starting from scratch by drawing up plans from a WW1 or 1920/1930's design. I considered the proposed Flitzer SSDR version, the Lincoln Sport and various other designs. I already had the Minimax drawings, and I obtained plans for the Lincoln Sport, Ragwing, Fly Baby, Isaacs Fury, Pietenpol, Pitts Special and others. Some of these aircraft clearly didn't meet the SSDR criteria but the drawings were obtained for design ideas. The aircraft that seemed to most closely match my criteria was the Nieuport 11 in 7/8 scale. Plans were available for an aluminium version and kits were also being produced. Consequently the weight and performance were known, and the aircraft could meet the SSDR criteria provided a suitable engine was selected. I obtained the plans for the aircraft from Circa Reproductions in Canada, only to be somewhat disappointed by the quality and lack of detail. Basically a set of sketches they bore no relation to the professional building plans for other types, particularly the Minimax I had already completed. Nevertheless many successful machines have been built to these drawings.

A kit version of the Nieuport 11 was available from Airdrome Aeroplanes in the U.S.A. Many of these aircraft are already flying and builder support is available, albeit weighted towards US builders. The Airdrome kit is based on the Circa plans but with a number of modifications, in particular replacement of the single main spar on the lower wing with a conventional two spar arrangement.

I decided to initially pursue the Circa plans route.

The design employs a simple aluminium tube method of construction held together by riveted aluminium gussets. Close inspection revealed that some measurements were missing from the plans and the location of some secondary components was omitted. Some builders would just dive in and start building, and this was the original philosophy of the design. Being somewhat more cautious, and used to the highly regulated environment in UK aviation, not to mention having some regard for my own life, I decided it would be prudent to redraw the plans. This would allow me to check all dimensions and highlight any errors or missing details.

The first stage therefore was to select a computer CAD program, and learn how to use it. Coming from Yorkshire ('Like a Scotsman but without the same same sense of generosity') I didn't want to pay a fortune (or anything if possible) and so looked at all the available free CAD software programs. Having experimented with a number of packages I eventually settled on Draftsight from Dassault Systemes. This is a free 2D application, with a 3D version (Solidworks) which is also free if you are a member of the Experimental Aircraft Association. Unfortunately the latter software does not run on my old Windows XP PC and so it would have meant upgrading. Consequently Draftsight it was. I found this very easy to use and was soon re-drafting the Circa plans. This revealed one critical measurement error (the location of the upper wing) and also highlighted a number of other rather subtle measurements that were easy to miss. Correspondence with other builders revealed that they had mistakes due to mis-reading the drawings.

Once the plans were redrawn on the computer I set about creating a bill of materials. This soon identified a critical problem. A key feature of the original Nieuport was the single spar in the lower wing, which resulted in the V-spar arrangement which makes the Nieuport designs so recognizable. The Circa plans specify an oval aluminium tube to give the necessary strength to this spar. Originally a suitable extrusion was sold as part of a kit of materials from a US supplier. However this item is no longer available and finding a suitable extrusion in the UK proved nigh impossible. The only alternate was to press a round section into an oval shape. I was not overly happy with this technique.

The aluminium tube method clearly allowed an aircraft to be built quickly but also provided a number of difficulties when it came to joining items such as turtledecks, controls, seats etc. to the round tube. Originally I had wanted to build in wood, and speed of construction was not a priority - this was to be a project to occupy my time and provide a challenge. I already had an aircraft and so was in hurry to get airborne. Another issue was that the plans were for a Nieuport look-alike. It was by no means an exact scale replica.

I gradually became less enthusiastic about aluminium construction and decided to explore a wooden version.

• A fundamental shift •

I decided to start again and to draw up plans for an exact 7/8 scale replica to be built in wood.

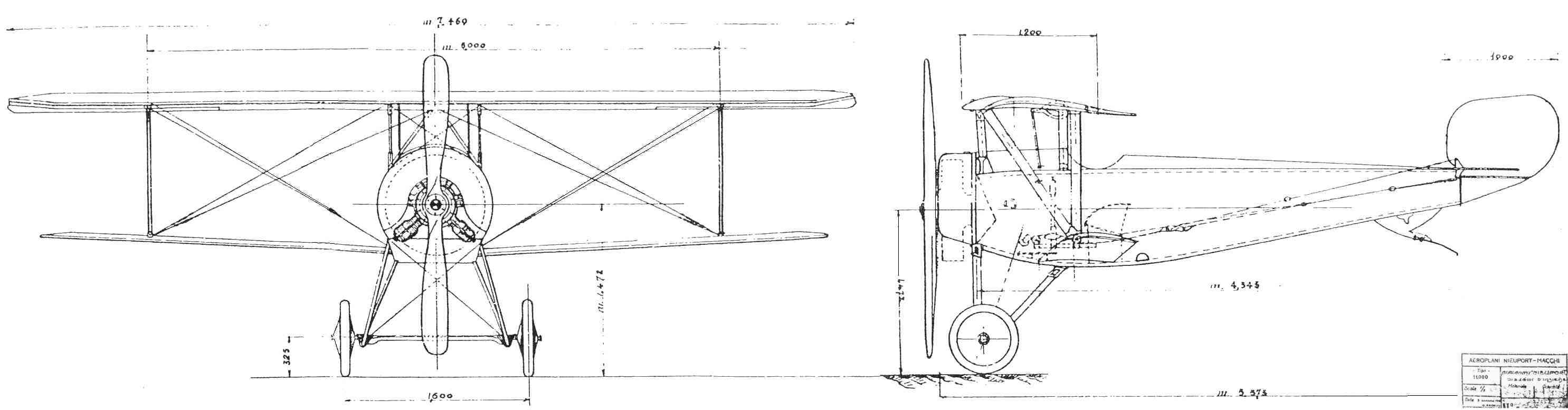

Stage 1 was to obtain original drawings. The only partial set available were for the Italian Macchi-Nieuport version, which differed slightly from the French version in having squared wingtips.

I also obtained the Nieuport 17 plans drawn by Rosendaal from a captured German machine. These included some details missing from the Macchi plans. The Nieuport 17 was simply a scaled up version of the Nie-11. Although seemingly highly accurate the Rosendaal drawings contain measurement errors, obviously due to manufacturing variances and the natural change in dimensions of wood in service.

I visited the Musee de l'Air in Paris and took photos of the only surviving Nieuport 11. Their research department also supplied drawings made from the machine during restoration. The museum example has been modified with the addition of a sprung tailskid, clearly as a result of broken tailskids in service.

During my WW1 research for my RFC website I copied numerous files from the National Archives in London showing modifications to Nieuport machines and reports on accidents and issues regarding the aircraft. Interestingly they show that the RFC/RAF experience with the oft criticised single lower spar arrangement was due entirely to manufacturing or maintenance issues rather than a fundamental design error as is often quoted in modern sources. The single lower spar offered a key advantage over a twin spar arrangement in that this was the method by which a nose heavy or tail heavy aircraft could be trimmed. Wedges were placed in the wing attachment bracket to change the incidence of the wing and adjust the trim.

I then set about redrafting the original drawings to 7/8 scale, although a number of changes had to be made to meet modern construction methods and aerodynamic experience.

The first of these was the airfoil section. The original Nieuport had an thin undercambered section typical of the period which resulted in a shallow spar. Modern airfoils are much more efficient and, being thicker without significant undercamber, allow for a deeper and thus much stronger spar. It made sense to copy the airfoil section used in the Circa design as this would result in a known performance. However the Circa section was a non-standard section, similar to the NACA 4412 section, but with the spars dropped down to the baseline in order to ease construction. It is mounted at 2 degrees of incidence and had a chord of 42". The ribs were tapered, getting shallower towards the wingtip. I examined similar airfoils and settled on the Rhode St Genesse 32. Wooden construction meant that it was not necessary to distort the section for an aluminium spar, but mount the front spar close to the deepest wing depth for maximum strength. This would be closer to the spar position on the original machine. This would give a superior performance to the Circa airfoil. It also meant that the V-struts and cabanes would attach directly to the spars, as on the original aircraft, rather than to compression struts per Circa. The scale chord was 41.5". Building the wooden ribs using the standard Warren girder principle on a jig meant it would be easier to make each rib the same size, rather than taper to the wingtip.

Secondly I decided to use aluminium airfoil section extrusions for the V-struts, rather than the wooden struts of the original. This meant I could use the same section for the cabane struts, V-struts and undercarriage. These struts are used on the UK Minimax and are supplied from a French company. Unlike many other streamline struts they include a tube inside the streamline section, providing extra strength and allowing a better attachment method, utilizing turned aluminium inserts that slot into the tube.

I then set about drafting the main components using the Draftsight CAD program. The wing structure was kept as close as possible to the Minimax, being a strong proven design, but with rib spacing the same as the original machine. The fuselage was also exact scale which was a complex shape, with curves towards the front, sharp tapers to the rear, and a V section when viewed from the front. Consequently a significant amount of bevelling and laminating would be necessary.

After the initial design was complete I assembled a bill of materials and calculated the weight of each item. This gave an empty weight of 160kg. Adding a pilot of 80kg and 30 litres of fuel (22kg) this gave an AUW of 262kg, well under the target of 300kg.

I estimated the centre of gravity of each main component and thus the CoG of the aircraft. This turned out to be too far aft.

As I couldn't reduce weight any further or distribute the weight in any alternative way, the obvious solution was to adjust the centre of pressure of the wing by increasing the sweep from 4 to 6 degrees. This was done retrospectively after the plans were drawn up and thus represented quite a lot of work in redrafting.

The Solidworks program is now offered free with EAA membership. Late in the construction process I upgraded my PC and used Solidworks to convert my 2D drawings to 3D.